What Are Bonds and How Do They Work?

A bond is a financial security that represents a loan made by an investor, known as the bondholder, to a borrower. Companies, sovereign governments, states and local municipalities regularly issue bonds to fund finance operations and special projects.

The loan, which is typically a long-term arrangement (10 years or more for government issues), is paid back when the bond matures. In the meantime, you, as the bondholder, typically receive fixed-rate interest payments, or coupons, on the loaned amount — commonly referred to as the principal or face value.

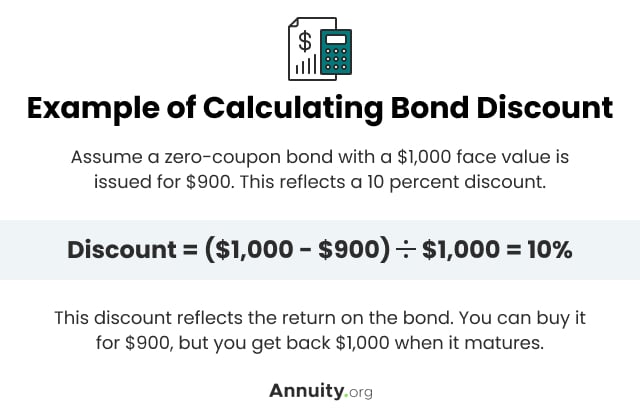

Usually, a bond makes coupon payments twice per year. Some bonds pay interest monthly, while some pay interest annually. Others, known as zero-coupon bonds, pay no periodic interest. The interest compensation on these instruments is offered via a discount of the face value.

The Bond Indenture

A bond indenture — a detailed legal document outlining the terms, clauses and covenants of the loan — governs a bond.

- Par Value

- The principal or face value of the bond, which the issuer agrees to repay at maturity.

- Maturity Date

- The date the principal will be repaid.

- Coupon Rate

- The annual interest rate to be paid.

- Coupon Payment Frequency

- The number of interest payments to be made in a year.

- Optionality

- The situations under which the issuer or bondholder may elect to change the terms of the agreement.

Items That Most Indentures Include

Let’s Talk About Your Financial Goals.

Example of a Bond

Assume the following:

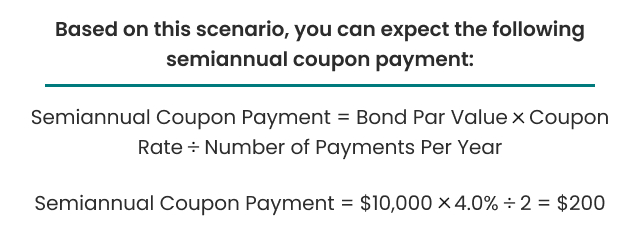

- You purchased a bond issued by Miller Corporation with a par value of $10,000 on Jan. 1, 2022.

- The bond has a 10-year term with a maturity date of Jan. 1, 2032.

- The coupon rate is 4.0 percent.

- Coupon payments are to be made semiannually on January 1 and July 1.

- There are no optionality clauses in the indenture.

Annualized, this produces $400 of interest income. If you hold the bond to maturity, you can expect to be paid $4,000 of interest over the 10-year term along with the return of your initial $10,000 investment on Jan. 1, 2032.

Types of Bonds

According to the Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association (SIFMA), the size of the global bond market is approaching $127 trillion. For U.S. issuers, the total is about $13.4 trillion.

This massive capital market consists of several types of bonds.

U.S. Treasuries

Given the full faith and backing of the U.S. government, these are the safest possible bond investments. They carry no credit risk, are extremely liquid and benefit from tax advantages at the state and local levels. U.S. Treasury instruments are categorized based on their maturities.

- Treasury Bills

- Treasury bills have maturities of 30 days to one year. Issues at the shortest end of the spectrum are considered to be completely free of all risks, including inflation.

- Treasury Notes

- Treasury notes have maturities between two and 10 years.

- Treasury Bonds

- Treasury bonds have maturities greater than 10 years. The longest term is 30 years, but longer terms have been considered in recent years.

- Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities (TIPS)

- TIPS offer a return that fluctuates with the rate of inflation.

Types of U.S. Treasury Instruments

U.S. Government Agency Bonds

Some agencies of the U.S. government are authorized to issue bonds. Issues are generally associated with housing-related agencies, like the Federal National Mortgage Association (Fannie Mae) and the Government National Mortgage Association (Ginnie Mae), which facilitate loans to home buyers.

While they exhibit minimal credit and liquidity risks, these instruments are subject to early repayment by homebuyers which exposes investors to reinvestment risk. Essentially, this is exposure to the possibility that you may be unable to reinvest cash flows received at a rate comparable to the current market interest rate.

Municipal Bonds

These bonds, commonly referred to as munis, are issued by states and local municipalities. Their level of risk varies depending on whether they are backed by specific projects (revenue bonds) or the general creditworthiness of the issuers (general obligation bonds). Typically, the former is less risky than the latter.

Regardless, even general obligation bonds are considered safe investments because of the issuers’ ability to raise money through taxes. That said, these instruments are not as safe as U.S. Treasuries or government agency bonds — they have a greater potential for default.

While they pose greater credit risk than Treasuries and agency bonds, they offer a tax advantage since many municipal issues are exempt from federal income tax as well as state income tax if you own munis in the state or locality you reside. Because of the favorable tax treatment, tax-exempt munis generally pay lower interest rates than otherwise comparable, taxable bonds.

Read More: Federal Tax Brackets

Corporate Bonds

These bonds are issued by companies across the investment grade and non-investment grade spectrum. Given an inherent level of credit risk, they generally pay higher interest rates than U.S. Treasury, government agency and municipal issues.

The additional interest, which is referred to as the yield premium, depends on the creditworthiness of the issuer, with riskier, non-investment-grade issuers paying much higher yields than the safest investment-grade issuers.

International Bonds

U.S. bonds only comprise about 39 percent of the global market. As of 2022, foreign governments and corporations had over $77 trillion of bond debt outstanding.

A large portion of this debt was funded by U.S. investors seeking meaningful diversification benefits and the opportunity to enhance the yield on their fixed-income holdings. That said, international bonds exhibit elevated levels of risk, especially in emerging markets.

Read More: Bearer Bonds

Purchasing Bonds as Investments

You can invest in bonds via primary markets or secondary markets. Primary markets are the forums where governments and corporations issue debt directly to investors for cash. Secondary markets are the forums where investors trade previously issued securities with each other.

Regardless of the way you purchase a bond, once acquired you can simply collect the bond’s interest payments until maturity. However, between the point of purchase and maturity, the bond’s market price is likely to fluctuate.

Price changes can be caused by several factors, including credit quality developments and interest rate movements. If you don’t intend to hold a bond until maturity, keeping tabs on these factors is critically important.

Learn More: Accrued Interest in Bonds

Key Risk Factors and Considerations

Credit Risk

The most obvious risk for many bonds is credit risk, which is exposure to financial loss caused by an issuer’s failure or refusal to make a promised payment. This risk is greatest when dealing with bond issuers that exhibit financial problems and questionable creditworthiness.

Creditworthiness ratings segregate bonds into two categories: investment grade and non-investment grade. Investment-grade bonds are of higher quality and generally offer lower interest rates than non-investment-grade bonds, which are commonly referred to as junk bonds.

You can check a bond’s credit rating by seeing how credit rating agencies have assessed them. Moody’s, Standard & Poor’s, and Fitch are the three credit rating agencies for bonds. An AAA rating is the highest rating, while a D rating is the lowest (Moody’s lowest rating is a C). A higher rating comes with less risk but also a lower yield.

Interest Rate Risk

Another major bond risk is interest rate risk. In many situations, this factor poses a greater threat than credit risk, but many investors underappreciated it.

Generally, as market interest rates rise, a bond’s price decreases. Conversely, as market rates fall, a bond’s price increases.

Assume you own a 4 percent coupon bond with a market price of $1,000 and the market interest rate for similar bonds suddenly increases from 4 percent to 5 percent.

Your bond will suddenly become less attractive, because investors can earn $50 per year on a new bond ($1,000 × 5% = $50) and only $40 per year on your bond ($1,000 × 4% = $40). The only way to make your bond comparable is to lower its price.

The extent of the price adjustment depends on the duration of the bond, which is a measure of the number of years it will take you to recoup your investment.

The longer the duration of a bond, the more sensitive its price will be to interest rate movements.

Liquidity Risk

Another prominent exposure is liquidity risk. This is the possibility of sustaining a significant loss due to the inability to sell a bond quickly at a fair price. Exposure can be difficult to measure because liquidity can appear adequate until adverse events, like the Great Recession and the COVID-19 virus, occur.

Bond Risk Impacts

Bonds can expose investors to a variety of other risks, but the exposures discussed above are the most notable. Concerning the impact they have on a bond’s interest rate, the following rules of thumb generally apply:

How Bond Risk Impacts Interest Rate

- High-quality bonds offer lower interest rates than low-quality bonds.

- Short-duration bonds offer lower interest rates than long-duration bonds.

- Highly liquid bonds offer lower interest rates than illiquid bonds.

Bond Investment Pros vs. Cons

Pros

- Generally safe investments that can serve as a stabilizing force in a portfolio.

- Provide a predictable source of fixed income.

- Investment grade instruments are highly liquid, especially U.S. Treasuries.

- Vast universe of bond issues provides opportunity for good diversification.

Cons

- Exposed to credit risk, which is the possibility of experiencing payment default.

- Can be highly sensitive to interest rate changes.

- Very low yielding since the Great Financial Recession of 2007.

- Relatively inferior option for investors with long investment horizons.

Bonds vs. Other Types of Investments

Like bonds, alternative investment vehicles can provide a dependable source of income to retirees and other yield-oriented investors, but they may pose unique risks.

5 Alternatives to Bonds

- Certificates of Deposit and High-Yield Savings Accounts

Certificates of deposit (CDs) are savings accounts offered by banks and credit unions. Generally, they offer higher interest rates than traditional savings accounts, but they lock up your money for varying periods. CDs also have fixed interest rates. - Bank Loans

These are floating-rate instruments that are well served as diversifiers to fixed-rate bonds. They are less exposed to interest rate movements and offer fairly high yields. While they are issued by non-investment grade companies, the credit risk associated with many bank loans is mitigated via pledged collateral. - Preferred Stocks

These are hybrid securities that have characteristics of both common stocks and bonds. They offer higher income than conventional stocks, but exhibit less volatility. - High-Dividend Common Stocks

These equity investments are focused on income, rather than price appreciation. In this respect, they are similar to bonds. While the risk profile of stocks is very different from that of bonds, high-dividend paying stocks have bond-like economic exposures. - Fixed Annuities

These are tax-advantaged financial contracts sold by insurance companies. They can be structured in a myriad of ways with a variety of features, but all fixed annuities involve an upfront payment by the investor in exchange for a series of guaranteed income distributions from the insurance company.

When comparing annuities vs. bonds, the most obvious difference is the nature of the relationship between you and the issuer. With an annuity, you are a party to a contract but with a bond, you are a lender.

Who Should Buy Bonds?

Like all financial decisions, contemplating whether or not it makes sense for you to invest in bonds is a highly personalized matter that depends on your unique situation and goals. Bonds could be an excellent investment for one person, but they could be a very poor choice for another. You should evaluate possible bond alternatives before settling on your investment vehicle.

That said, bonds are generally a good investment for income-focused investors. They make even more sense for investors with a relatively low tolerance for risk. Oftentimes, these characteristics relate to retirees that have begun to draw down on their hard-earned savings. Retirees have a relatively short investing horizon, and they can’t withstand extreme levels of volatility. Moreover, to support their lifestyle, they assign a high value to assets, like bonds, that produce income.